It is well documented that obesity may cause hypogonadism, and that hypogonadism may cause obesity [1-4] This has generated debate about what condition comes first; obesity or hypogonadism? And what should be the first point of intervention?

In this article I will summarize data from several reviews on the associations of hypogonadism and obesity [1-4], and make the case that these conditions create a self-perpetuating vicious circle. Once a vicious circle has been established, it doesn’t matter where one intervenes; one can either treat the obese condition or treat hypogonadism first. The critical issue is to break the vicious circle as soon as possible before irreversible health damage arises.

Nevertheless, as I will explain here, treating hypogonadism first with testosterone replacement therapy may prove to be a more effective strategy because it to a large extent “automatically” takes care of the excess body fat and metabolic derangements. In addition, treating hypogonadism first also confers psychological benefits that will help obese men become and stay more physically active.

Key Points [1-4]

• Traditional obesity treatments with diet and exercise programs are notorious for failing in long-term maintenance of weight loss due to lack of adherence. Anti-obesity drugs have limited efficacy and may not be without adverse effects.

• In the prospective Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS), non-obese men who became obese had a decline of testosterone levels comparable to that of 10 years of aging.

• Testosterone deficiency and obesity each contribute independently to a self-perpetuating vicious cycle.

• Long-term testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism improves body composition, metabolic syndrome components and quality of life, and thereby can help break the vicious cycle.

• Treatment of hypogonadism with long-term testosterone therapy, with or without lifestyle modifications, effectively treats obesity by correcting testosterone deficiency; one physiological root cause of obesity.

• In contrast to the U-shaped curve for weight loss seen with traditional obesity treatments, which are characterized by weight loss and weight regain, treatment with testosterone therapy results in a continuous reduction in obesity parameters (waist circumference, weight and BMI) for >5 years, or until metabolic abnormalities return to healthy ranges.

• The significant effectiveness of testosterone therapy in combating obesity in hypogonadal men remains largely unknown to doctors. Educational efforts are therefore critical to bring research findings into clinical practice in order to improve patient care and health outcomes.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Obesity, classified by the American Medical Association in 2013 as a disease, is an epidemic that is rapidly spreading globally. Obesity is the most common preventable disease and the most common modifiable risk factor for several chronic diseases [5, 6]; it is notable that obesity is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease [7, 8] and type 2 diabetes [9, 10], as well as an independent cause of increased morbidity and mortality.[5] With the contemporary pervasive unhealthy food habits and sedentary lifestyles, it is anticipated that the prevalence of obesity and its health consequences will continue to rise.[11] Over the last decade, an escalation in diabetes incidence has paralleled the rapid increase in obesity prevalence, constituting a global health crisis.[12] The concurrent occurrence of obesity and diabetes in the same individual, known as “diabesity” is also rising in prevalence at a fast pace.[13, 14]

A comprehensive program of lifestyle modification can produce a 7% to 10% reduction of body weight and clinically meaningful improvements in several cardiovascular risk factors, including the prevention of type 2 diabetes.[15] However, long-term maintenance of lifestyle induced weight loss is notoriously difficult and fails for the large majority.[16] In turn, anti-obesity drugs have limited efficacy and adverse side effects that limit their use.[5, 17]

Thus, few effective treatment options for lasting weight loss are available to obese individuals. This is a serious issue, as obesity is an escalating epidemic posing a tremendous burden on both the individual and public level. According to a recently published report “Overcoming obesity: An initial economic analysis” from the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI),” obesity is one of the top three preventable social burdens (along with smoking and violence/war/terrorism) generated by human beings” imposing an estimated annual global direct economic burden amounting to 2 trillion USD.[18]

Therefore, new interventions are urgently needed to combat this alarming preventable threat to society. A new line of reasoning has suggested that it is time to test hormonal theories about why people get fat.[19] Testosterone is a promising candidate.

WHAT NEW STUDIES SHOW

Multiple lines of evidence, from experimental to observational studies, and randomized controlled trials of both testosterone therapy and testosterone deprivation, show the critical role of testosterone in regulation of body fat metabolism and body composition.[1-4]

Obesity as a cause of hypogonadism – Evidence that obesity leads to low testosterone

Multiple observational studies in community-dwelling men suggest that obesity leads to decreased testosterone. Cross-sectional analyses show that obese men have lower testosterone levels than age-matched non-obese men.[20, 21] In the prospective Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS), non-obese men who became obese had a decline of testosterone levels comparable to that of 10 years of aging.[22] Another prospective study confirmed that weight gain results in a proportional decrease in testosterone levels at follow-up.[23] Obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and dyslipidaemia have been identified as risk factors of incident hypogonadism.[24]

Support that obesity is a cause of hypogonadism comes from studies of weight loss (induced by either low-calorie dieting or bariatric surgery) which show increases in testosterone levels proportional to the amount of weight lost.[25]

Hypogonadism as a cause of obesity – Evidence that low testosterone leads to obesity

There is also ample evidence, both from experimental and human studies, to suggest the reverse. Lower baseline testosterone levels independently predict an increase in intra-abdominal fat after 7.5 years of follow-up.[26] Experimental induction of hypogonadism in healthy men aged 20-50 years, significantly increases body fat mass within 16 weeks, indicating that severe testosterone deficiency rapidly causes body fat gain.[27] Moreover, men with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy show marked increases in total body fat mass and abdominal visceral fat within 6 months.[28]

Further proof of the causal role of testosterone in the pathogenesis of obesity comes from a growing number of studies showing that testosterone therapy significantly reduces several markers of obesity, (including weight, waist circumference and BMI)[29-33], total body fat mass [34-39] and intra-abdominal fat mass.[39-42]

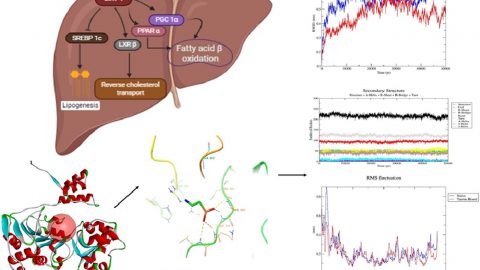

While testosterone is most known for its effect on libido and sexual function, it plays a key role in fat, carbohydrate and protein metabolism as well.[39, 43-47] The exact mechanisms by which testosterone acts on pathways to control metabolism are not fully clear. Nevertheless, data from animal, cell and clinical studies show that testosterone at the molecular level controls the expression of important regulatory proteins involved in energy and substrate metabolism.[43] The cumulative effects of testosterone on these biochemical pathways would account for the overall benefits seen with testosterone therapy on fat loss and body composition.

Low testosterone and obesity: a self-perpetuating vicious cycle

When taking into consideration both sides of the testosterone – obesity link, it becomes clear that a bidirectional relationship exists between testosterone and obesity, initiating and reinforcing a self-perpetuating cycle (figure 1).

Figure 1: Bidirectional relationship between low testosterone and obesity, initiating and reinforcing a self-perpetuating cycle. Click to see full image.

Figure 1: Bidirectional relationship between low testosterone and obesity, initiating and reinforcing a self-perpetuating cycle. Click to see full image.

On the one hand, increasing body fat suppresses the HPT (hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal) axis by multiple mechanisms; via increased insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and diabetes [48, 49], and elevation in estradiol and cortisol levels.[50, 51] Because of its mechanistic and clinical evidence, it has been suggested that obesity-induced hypogonadism should be regarded as a distinct clinical entity and subtype of (hypogonadotrophic) hypogonadism.[52]

On the other hand, low testosterone promotes accumulation of total and visceral fat mass, thereby inducing and/or exacerbating the gonadotropin inhibition, which will further reduce testosterone levels.[48, 50, 51] Testosterone may exert a bi-phasic effect on metabolism; an acute improvement in insulin sensitivity that occurs rapidly within a few days to few weeks of treatment, before loss of fat mass becomes evident; and a long-term effect achieved when a significant reduction of total and visceral body fat occurs.[2]

A recent placebo-controlled study investigated the effects of testosterone therapy on obesity, HbA1c, hypertension and dyslipidemia in hypogonadal diabetic patients.[53] It was found that testosterone therapy did break the metabolic vicious circle by raising testosterone levels, and it was concluded that re-instituting physiological levels of testosterone has an important role in reducing the prevalence of diabetic complications.[53]

Psychological effects – Adherence to lifestyle changes

Testosterone therapy as an obesity treatment confers additional benefits in that it consistently improves mood and feelings of energy, and reduces fatigue [54-58]; this in turn may bolster motivation to adhere to diet and exercise regimens designed to combat obesity.[2] This has been demonstrated in studies that added testosterone or placebo to diet and exercise recommendations or structured programs.[59, 60]

In one study the placebo group showed initial reduction in waist circumference after 18 weeks, but it returned toward baseline as soon as 12 weeks later, indicating the transient effect of the physician’s advice to improve life style.[59] In another study, adding testosterone therapy to a 1 year-long supervised diet and exercise program resulted in greater improvements in testosterone levels, waist circumference, glycosylated hemoglobin HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), triglyceride levels, compared to the placebo group that was on the same diet and exercise program. [60] The larger reduction in waist circumference by adding testosterone to a diet + exercise program, compared to the same diet + exercise program alone, is especially notable (figure 2).[60]

Figure 2: Waist circumference in 32 men with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes in the DIMALITE (Diabetes Management by Lifestyle and Testosterone) study. Click to see full image.

Figure 2: Waist circumference in 32 men with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes in the DIMALITE (Diabetes Management by Lifestyle and Testosterone) study. Click to see full image.

It has been suggested that hypogonadism is “the common denominator between the development of insulin resistance in the long term and the immediate experience of fatigue”.[61] Androgens, by improving mitochondrial function, control the sense of energy and vitality, and the “pick-up-and-go” mentality, as well as possibly influences the pathogenesis of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.[61] Therefore, testosterone therapy, by addressing a root cause of obesity, can help obese men adhere to exercise programs and thereby not only break the vicious circle, but also initiate a health promoting circle.

CONCLUSION and COMMENTS

Restoring testosterone levels in hypogonadal obese men will relatively quickly break the self-perpetuating vicious circle, and transform it into a “health promoting circle.” And restoring testosterone levels in hypogonadal men who are not yet obese may help prevent excess body fat accumulation and thereby serve as a primary prevention strategy. I will outline the promising results of using testosterone replacement therapy as a primary prevention strategy in an upcoming article.

It is of utmost interest that in contrast to the U-shaped curve for weight loss seen with traditional obesity treatments, which are characterized by weight loss and weight regain, treatment with testosterone therapy results in a continuous reduction in obesity parameters (waist circumference, weight and BMI) for >5 years, or until metabolic abnormalities return to healthy ranges.[29-33]

Testosterone therapy has been proposed to be a new potential obesity treatment modality in hypogonadal men with excessive body fat mass and metabolic derangements.[2] It should be underscored that the contribution of testosterone therapy to combating obesity remains largely unknown to medical professionals.[2] It is therefore important to highlight the promising research on the anti-obesity effects of testosterone therapy and help implement its research findings into clinical practice, for the benefit of a growing population of suffering hypogonadal men.

References:

1. Ng Tang Fui, M., P. Dupuis, and M. Grossmann, Lowered testosterone in male obesity: mechanisms, morbidity and management. Asian J Androl, 2014. 16(2): p. 223-31.

2. Saad, F., et al., Testosterone as potential effective therapy in treatment of obesity in men with testosterone deficiency: a review. Curr Diabetes Rev, 2012. 8(2): p. 131-43.

3. Saad, F. and L.J. Gooren, The role of testosterone in the etiology and treatment of obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus type 2. J Obes, 2011. 2011.

4. Traish, A.M., Testosterone and weight loss: the evidence. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes, 2014. 21(5): p. 313-22.

5. Patham, B., D. Mukherjee, and Z.T. San Juan, Contemporary review of drugs used to treat obesity. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem, 2013. 11(4): p. 272-80.

6. Van Gaal, L.F., I.L. Mertens, and C.E. De Block, Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature, 2006. 444(7121): p. 875-80.

7. Hubert, H.B., et al., Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 1983. 67(5): p. 968-77.

8. Poirier, P., et al., Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation, 2006. 113(6): p. 898-918.

9. Chan, J.M., et al., Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care, 1994. 17(9): p. 961-9.

10. Sung, K.C., et al., Combined influence of insulin resistance, overweight/obesity, and fatty liver as risk factors for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2012. 35(4): p. 717-22.

11. Bhurosy, T. and R. Jeewon, Overweight and Obesity Epidemic in Developing Countries: A Problem with Diet, Physical Activity, or Socioeconomic Status? ScientificWorldJournal, 2014. 2014: p. 964236.

12. Colagiuri, S., Diabesity: therapeutic options. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2010. 12(6): p. 463-73.

13. Farag, Y.M. and M.R. Gaballa, Diabesity: an overview of a rising epidemic. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2011. 26(1): p. 28-35.

14. Kral, J.G., Diabesity: palliating, curing or preventing the dysmetabolic diathesis. Maturitas, 2014. 77(3): p. 243-8.

15. Wadden, T.A., et al., Lifestyle modification for obesity: new developments in diet, physical activity, and behavior therapy. Circulation, 2012. 125(9): p. 1157-70.

16. Wing, R.R. and S. Phelan, Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr, 2005. 82(1 Suppl): p. 222S-225S.

17. Rueda-Clausen, C.F., R.S. Padwal, and A.M. Sharma, New pharmacological approaches for obesity management. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2013. 9(8): p. 467-78.

18. Dobbs, R., et al., Overcoming obesity: An initial economic analysis http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/economic_studies/how_the_world_could_better_fight_obesity Accessed December 1, 2014.

19. Taubes, G., Treat obesity as physiology, not physics. Nature, 2012. 492(7428): p. 155.

20. Yeap, B.B., et al., Lower serum testosterone is independently associated with insulin resistance in non-diabetic older men: the Health In Men Study. Eur J Endocrinol, 2009. 161(4): p. 591-8.

21. Tajar, A., et al., Characteristics of androgen deficiency in late-onset hypogonadism: results from the European Male Aging Study (EMAS). J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2012. 97(5): p. 1508-16.

22. Travison, T.G., et al., The relative contributions of aging, health, and lifestyle factors to serum testosterone decline in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2007. 92(2): p. 549-55.

23. Camacho, E.M., et al., Age-associated changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular function in middle-aged and older men are modified by weight change and lifestyle factors: longitudinal results from the European Male Ageing Study. Eur J Endocrinol, 2013. 168(3): p. 445-55.

24. Haring, R., et al., Prevalence, incidence and risk factors of testosterone deficiency in a population-based cohort of men: results from the study of health in Pomerania. Aging Male, 2010. 13(4): p. 247-57.

25. Corona, G., et al., Body weight loss reverts obesity-associated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol, 2013. 168(6): p. 829-43.

26. Tsai, E.C., et al., Low serum testosterone level as a predictor of increased visceral fat in Japanese-American men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord, 2000. 24(4): p. 485-91.

27. Finkelstein, J.S., et al., Gonadal steroids and body composition, strength, and sexual function in men. N Engl J Med, 2013. 369(11): p. 1011-22.

28. Hamilton, E.J., et al., Increase in visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2011. 74(3): p. 377-83.

29. Haider, A., et al., Hypogonadal obese men with and without diabetes mellitus type 2 lose weight and show improvement in cardiovascular risk factors when treated with testosterone: An observational study. Obes Res Clin Pract, 2014. 8(4): p. e339-49.

30. Haider, A., et al., Effects of long-term testosterone therapy on patients with “diabesity”: results of observational studies of pooled analyses in obese hypogonadal men with type 2 diabetes. Int J Endocrinol, 2014. 2014: p. 683515.

31. Saad, F., et al., Long-term treatment of hypogonadal men with testosterone produces substantial and sustained weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring), 2013. 21(10): p. 1975-81.

32. Traish, A.M., et al., Long-term testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men ameliorates elements of the metabolic syndrome: an observational, long-term registry study. Int J Clin Pract, 2014. 68(3): p. 314-29.

33. Yassin, A. and G. Doros, Testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men results in sustained and clinically meaningful weight loss. Clin Obes, 2013. 3(3-4): p. 73-83.

34. Page, S.T., et al., Exogenous testosterone (T) alone or with finasteride increases physical performance, grip strength, and lean body mass in older men with low serum T. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2005. 90(3): p. 1502-10.

35. Snyder, P.J., et al., Effect of testosterone treatment on body composition and muscle strength in men over 65 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1999. 84(8): p. 2647-53.

36. Kenny, A.M., et al., Effects of transdermal testosterone on bone and muscle in older men with low bioavailable testosterone levels. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2001. 56(5): p. M266-72.

37. Wittert, G.A., et al., Oral testosterone supplementation increases muscle and decreases fat mass in healthy elderly males with low-normal gonadal status. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2003. 58(7): p. 618-25.

38. Wang, C., et al., Transdermal testosterone gel improves sexual function, mood, muscle strength, and body composition parameters in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2000. 85(8): p. 2839-53.

39. Sattler, F., et al., Testosterone Supplementation Improves Carbohydrate and Lipid Metabolism in Some Older Men with Abdominal Obesity. J Gerontol Geriatr Res, 2014. 3(3): p. 1000159.

40. Marin, P., et al., Androgen treatment of abdominally obese men. Obes Res, 1993. 1(4): p. 245-51.

41. Marin, P., et al., The effects of testosterone treatment on body composition and metabolism in middle-aged obese men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord, 1992. 16(12): p. 991-7.

42. Allan, C.A., et al., Testosterone therapy prevents gain in visceral adipose tissue and loss of skeletal muscle in nonobese aging men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2008. 93(1): p. 139-46.

43. Kelly, D.M. and T.H. Jones, Testosterone: a metabolic hormone in health and disease. J Endocrinol, 2013. 217(3): p. R25-45.

44. Frederiksen, L., et al., Testosterone therapy increased muscle mass and lipid oxidation in aging men. Age (Dordr), 2012. 34(1): p. 145-56.

45. Petersson, S.J., et al., Effect of testosterone on markers of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and lipid metabolism in muscle of aging men with subnormal bioavailable testosterone. Eur J Endocrinol, 2014. 171(1): p. 77-88.

46. Griggs, R.C., et al., Effect of testosterone on muscle mass and muscle protein synthesis. J Appl Physiol (1985), 1989. 66(1): p. 498-503.

47. Brodsky, I.G., P. Balagopal, and K.S. Nair, Effects of testosterone replacement on muscle mass and muscle protein synthesis in hypogonadal men–a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1996. 81(10): p. 3469-75.

48. Grossmann, M., Low testosterone in men with type 2 diabetes: significance and treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2011. 96(8): p. 2341-53.

49. Pitteloud, N., et al., Increasing insulin resistance is associated with a decrease in Leydig cell testosterone secretion in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2005. 90(5): p. 2636-41.

50. Mah, P.M. and G.A. Wittert, Obesity and testicular function. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2010. 316(2): p. 180-6.

51. Cohen, P.G., The hypogonadal-obesity cycle: role of aromatase in modulating the testosterone-estradiol shunt–a major factor in the genesis of morbid obesity. Med Hypotheses, 1999. 52(1): p. 49-51.

52. Saboor Aftab, S.A., S. Kumar, and T.M. Barber, The role of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the development of male obesity-associated secondary hypogonadism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2013. 78(3): p. 330-7.

53. Janjgava, S., et al., Influence of testosterone replacement therapy on metabolic disorders in male patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and androgen deficiency. Eur J Med Res, 2014. 19(1): p. 56.

54. Amanatkar, H.R., et al., Impact of exogenous testosterone on mood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Ann Clin Psychiatry, 2014. 26(1): p. 19-32.

55. Spitzer, M., et al., The effect of testosterone on mood and well-being in men with erectile dysfunction in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Andrology, 2013. 1(3): p. 475-82.

56. Wang, C., et al., Testosterone replacement therapy improves mood in hypogonadal men–a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1996. 81(10): p. 3578-83.

57. Jockenhovel, F., et al., Comparison of long-acting testosterone undecanoate formulation versus testosterone enanthate on sexual function and mood in hypogonadal men. Eur J Endocrinol, 2009. 160(5): p. 815-9.

58. Jockenhovel, F., et al., Timetable of effects of testosterone administration to hypogonadal men on variables of sex and mood. Aging Male, 2009. 12(4): p. 113-8.

59. Kalinchenko, S.Y., et al., Effects of testosterone supplementation on markers of the metabolic syndrome and inflammation in hypogonadal men with the metabolic syndrome: the double-blinded placebo-controlled Moscow study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2010. 73(5): p. 602-12.

60. Heufelder, A.E., et al., Fifty-two-week treatment with diet and exercise plus transdermal testosterone reverses the metabolic syndrome and improves glycemic control in men with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes and subnormal plasma testosterone. J Androl, 2009. 30(6): p. 726-33.

61. Traish, A., B. Abdallah, and G. Yu, Androgen deficiency and mitochondrial dysfunction: implications for fatigue, muscle dysfunction, insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. . Horm Mol Biol Clin Invest 2011. 8: p. 431–444.

Wow, once again, the evidence for Low-T therapy’s effectiveness keeps growing! Thanks, Monica and Will, for opening our eyes on this critical problem. My difficulty in finding a clinic is because I’m on Medicaid and the clinics in this metroplex, from my research so far, are limited to some insurance programs and out-of-pocket. I’m not giving up, however! The search will continue.

That’s great Kent; never give up!

Hopefully telemedicine will become the new standard of care in the near future; that will make it easier for men to get in touch with good doctors, regardless of geographic location.

Great article Monica, as usual. I just hope if T therapy is used, the individual who gets it, then actively makes the most of it and participates in a resistance type of training plan. Otherwise, my fear is, they just rely solely on the T therapy, and continue their errant lifestyle! Thanks again.

Thank you.

Yes, combining TRT with lifestyle changes is the ultimate way to improve health and wellbeing.

Implementing lifestyle changes is hard for most people; as described in the article, testosterone can help men get over that initial barrier.

Well done piece, as usual….Would only add that for those who do supplement T that it is important to follow bloodwork to ensure Hct doesn’t get too high, and that the bioavailable T is is high normal range..and no more. Also, know that this will be a lifetime commitment, as exogenous T will shut down testes production in most of this subject cohort, for good….

DJS MD,JD

Thank you.

Yes, for majority of men, TRT is a lifelong treatment. And like you said, clinical monitoring is essential.

In older men, Leydig function is already impaired, so there is not much “shut down” to fuss about.

This article is spot on. I feel that if older men would get this type of treatment, prostate problems would not be an issue any longer. But alas, FIND a doctor who understands and is willing to give this type of treatment.

Thank you. Yes, conservatism in medicine is causing a lot of unnecessary suffering.

When it comes to the prostate, it is excessive body fat and chronic low grade inflammation etc that is dangerous, not testosterone!

Nice Article.Thanks for the information

Great article.Well done.